The last time I was this terrified in the Royal College of Music was in 1963. In those far-off days children did their instrumental exams not in local centres but in the country’s great music conservatoires. Thus it was that the eight-year-old Morrison, clutching his grade 3 piano pieces, was thrust into a basement room in this grandiose South Kensington edifice to be confronted by none other than Herbert Howells, who still examined for the Associated Board even though he was quite a famous composer by then. All I remember is trying to stop my hands from shaking enough to press the ivories down in any order at all. Howells, a kindly old man, gave me a merit, probably for perseverance.

Now, 61 years later in the basement of the same building, I am experiencing identical sensations — panic, nausea, shaking intermingled with paralysis, and the feeling that someone has removed what remains of my brain and inserted soggy blotting paper in its place.

How did this nightmare start? I had been led into a kind of vestibule kitted out to resemble the backstage area of a concert hall — right down to the faint murmur of an expectant audience. “Ready to go?” asked Aaron Williamon, the head of the RCM’s Centre for Performance Science. Then the door swung open, and I lurched unsteadily forward into a glare of spotlights and a daunting Steinway in the middle of the room. A burst of applause greeted me and suddenly I realised I was staring at a full auditorium of punters.

Of course they weren’t really there. What I was actually seeing was a huge video screen, floor to ceiling and about 10m across, depicting about 100 “avatar” spectators. But boy, they seemed real. I sat down at the Steinway, took a deep breath and plunged into Irving Berlin’s Cheek to Cheek — a piece I had chosen to put the maximum distance, culturally, between me and the brilliant teenage virtuoso pianists who usually whizz through Rachmaninov and Chopin in this place.

Well, they seemed to like it. The avatars, I mean. As I finished some of them even rose to their feet to cheer. Then I noticed George Waddell, the RCM’s performance research and innovation fellow, swiftly tapping instructions into an iPad. The illusion of this standing ovation, I realised, was all his doing. I wasn’t the next Lang Lang, just a very traumatised journalist. “Well done,” Waddell said. “How do you feel? Like you’ve been through the real thing?”

Actually, I’ve never been through the real thing — never given a piano recital in a packed concert hall, oddly enough — so the question was impossible to answer. But many of the RCM’s students have never been through the real thing either. Most of these young musicians will have spent years practising by themselves or with their tutors, or performing to small gatherings of fellow students.

Psychologically, the step up to giving a real performance to a real paying audience is immense. Suddenly, the body and brain are confronted by pressures, anxieties and nerves that the performer has never experienced before. It’s to prepare students for that shock that the RCM has built this extraordinary new Performance Laboratory.

• Stage fright and the pandemic: the new epidemic facing theatres

It has been years in development, funded by a £1.9 million grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the World Class Laboratories Fund. And it certainly doesn’t come out of the blue. The RCM has been running a Centre for Performance Science since 2000, and since 2015 has done so in partnership with Imperial College London, the science and technology hothouse next door. “Performance in this instance doesn’t just mean music or even just the arts,” Williamon says. “Researching how we perform under pressure is increasingly of vital importance to people in business, education, medicine, science and sport. The technology that we are using in this room can aid progress in all those fields.”

The technology is certainly jaw-dropping. The sort of visual-graphics engines that drive the latest video games have been used to simulate not just several different shapes and sizes of auditorium but also the variety of audiences that a performer might encounter — and all the off-putting sounds, from a bout of coughing to the inevitable pinging of a mobile phone, that they make. And the way audience behaviour is going, particularly at musicals, there will soon have to be an option for recreating drunken fisticuffs in the stalls.

With another flick of his iPad, Waddell replaces the audience who had generously acclaimed me with a much sniffier bunch of avatars: four unsmiling adjudicators, such as a student might encounter at an audition or a competition. One of them even interrupts performances to say “thank you, we’ve heard enough” — probably the five most chilling words any young musician will ever receive.

The technology controlling the acoustics is just as advanced. What was formerly a bare-walled performance studio has been transformed by something called the Meyer Sound Constellation system into … well, practically any level of reverberation and sonic ambience that students are likely to encounter, whether they are performing in St Paul’s Cathedral, Carnegie Hall, La Scala in Milan or (more practically) a local music club in a school hall.

“It combines ambient sensing microphones, advanced digital signal processing and loudspeakers embedded in the walls that can completely change the reverberation,” says Richard Bland, the RCM’s head of digital and production. In 20 years, perhaps, every concert hall will have this level of reverberation flexibility, but right now this is pretty special.

And the piano on which I’ve just bashed out my Cheek to Cheek also turns out to have a bag of tricks. “It can play back your performance or be played remotely,” Waddell says. “That’s really useful for online masterclasses.” As if by magic the keyboard starts to play itself and sublime sounds tinkle out. “That’s one we prepared earlier — Lang Lang,” Waddell says.

• Stage fright drove Olivia Colman to hypnotherapy

Along with all the visible technology, however, is the more intimate stuff that measures what effect a performance is having on the performer. That starts, of course, with a tutor’s visual assessment of a student’s body language on the stage — a crucial aspect of any performance. If a performer looks nervous, awkward and worried, the audience feels uncomfortable too.

But the RCM is also a world leader in the science of performance, measuring heart rates, perspiration, adrenaline levels, saliva. All those can indicate how students are handling pressure and what techniques and strategies they need to channel the stress positively rather than letting it turn the body into a quivering jelly. And that sort of insight can be invaluable in all sorts of jobs. Already the RCM and Imperial have honed the performance skills of professionals from organisations as diverse as Google and the Football Association.

I left the RCM’s Performance Laboratory still shaking like a leaf but in no doubt that it could have a really beneficial effect on how students approach performance, and how they quell their nerves without recourse to the sadly all too common use of beta blockers or other chemical remedies. What it won’t do, of course, is ensure that when those students leave college they will encounter real concert halls packed with real audiences waiting to acclaim them. It would be a tragedy if performing to a wall of madly cheering avatars proved to be the highlight of their solo careers — as it has of mine.

By Blanca Schofield

Adele

The queen of heartbreak now performs most nights in her lucrative Las Vegas residency, so you wouldn’t know she experienced nerves. But think again. “I get shitty scared,” she told Rolling Stone in 2011, adding that she once escaped out of the fire exit in Amsterdam and projectile-vomited on the audience in Brussels. Encore! Not.

Daniel Day-Lewis

Now officially retired from acting, the Englishman has never shied away from a tricky role. Note, however, that since 1989 he has only appeared on screen: that year he quit a production of Hamlet amid reports that he had seen a ghost. He later clarified to Time magazine: “It was communication with my own dead father … but I don’t remember seeing any ghosts!”

Laurence Olivier

After decades in the public eye, Olivier started suffering from stage fright while playing Othello in his fifties. His coping strategies included asking Iago to stay visible through his soliloquies and telling actors not to look him in the eye. “This made me feel that there was not quite so much loaded against me,” he said.

Carly Simon

Among the most unusual remedies are those adopted by the You’re So Vain singer. In 1981 Simon was so struck by nerves in Pittsburgh that fans came on stage to rub her arms and legs. And in 1996, before a 50th birthday concert for Bill Clinton, she asked her band’s horn section to spank her. Whatever works.

Roberto Alagna

There can be no worse feeling than hearing booing, but the French tenor was not going to take it lying down. In 2006, Alagna stormed off stage at La Scala, halfway through an aria in Franco Zeffirelli’s production of Aida, declaring: “I do not deserve this kind of reception.” His understudy rushed on in jeans. The show must go on.

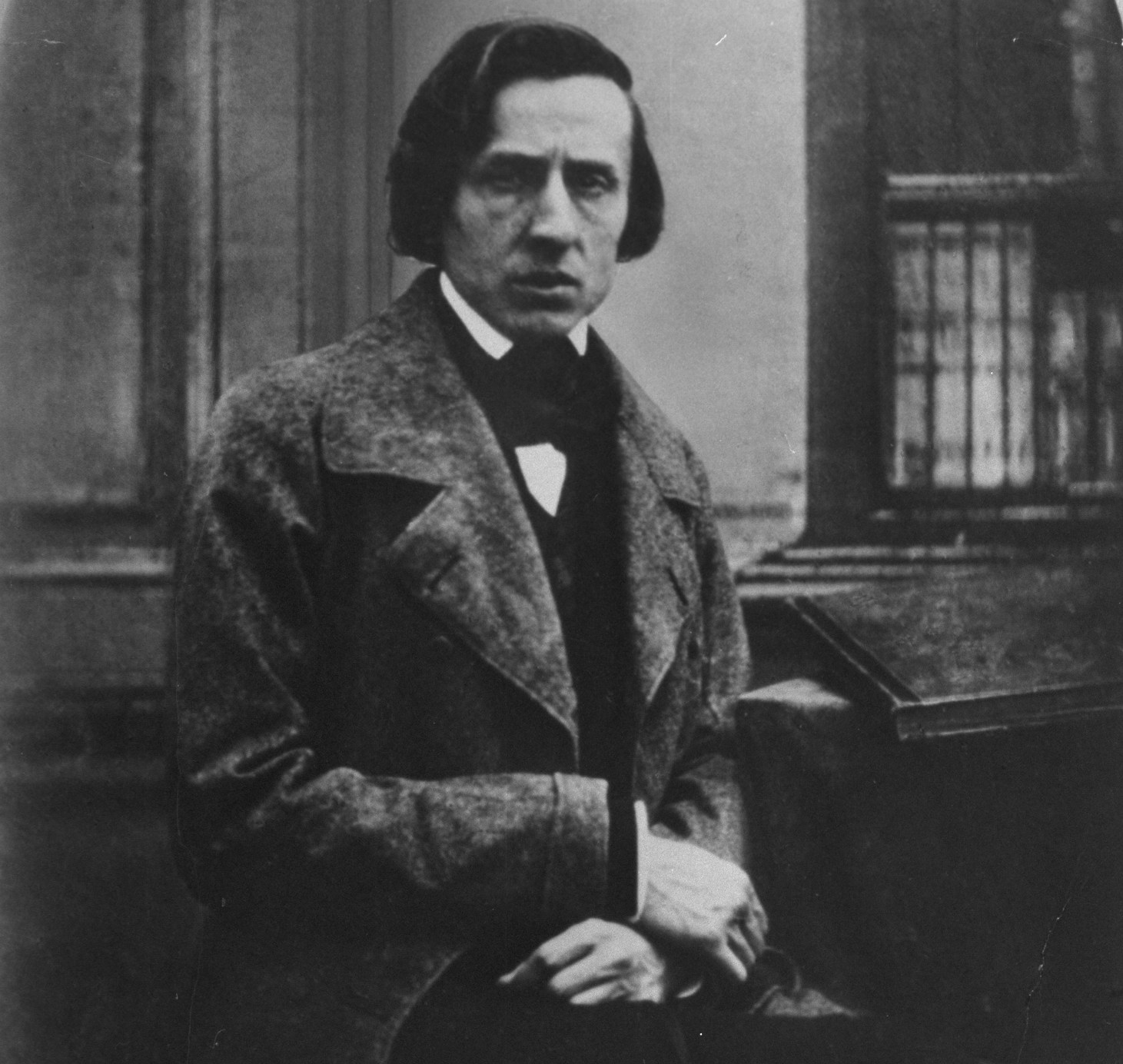

Fryderyk Chopin

The Polish composer disliked big crowds, so much so that he gave only 30 public performances, the final one when he was 26. His contemporary Franz Liszt recalled him saying: “An audience intimidates me. I feel asphyxiated by its eager breath, paralysed by its inquisitive stare, silenced by its alien faces.”